Friday, October 28, 2016

OED ≠ Optimal Explosive Device

In a conversation I heard this week between Krista Tippett, Eboo Patel (founder of the Interfaith Youth Core) and former U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey, Patel spoke eloquently about his upbringing, especially his own experience as a college student. He talked about the passion he developed around racial issues and how avidly he promoted his causes. He confessed to being caught up in binary thinking -- right/wrong -- clear distinctions. He made it clear, however, that he no longer adhered to that way of thinking. He related a much more nuanced way of thinking, using "justice" as an example:

Justice is another term that we assume everybody has the same definition of. My new line to 20-year-olds who look very chastised when I say this on campuses is, “If everybody in the room that you’re in has the same definition of ‘justice’ that you do — I don’t care how many colors, or genders, or sexual preferences, or religions are in that room — it’s not a diverse room.” Part of the definition of “diversity” is the recognition there are diverse understandings of justice.

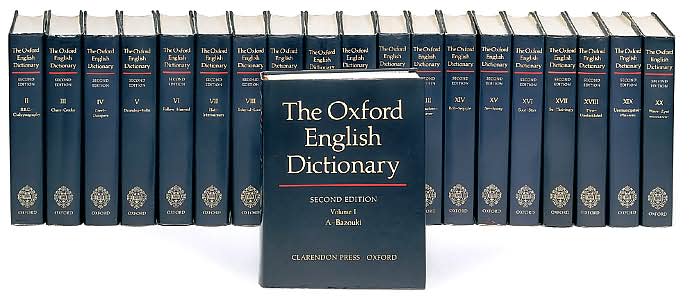

Tippet then shifted the focus to Tretheway, asking her opinion. And she replied: "I was thinking that what Eboo was saying was exactly right. But for a moment, I longed to be standing in front of my OED with my little magnifying glass so that I could look up that word “justice” again." Whether Tretheway meant it this way, what I immediately thought (after running "OED" past the filter of "IED" --"Improvised Explosive Device") was that recourse to the OED could be seen as a turn to a single authoritative definition of "justice". And, following on that would be the assumption that the correct definition of "justice" could then be used as a bludgeon to use with those who disagreed.

I'm not very much interested in the conversation about whether or not there is an objective "truth" (or an objective "justice"); competing truth claims rarely get us anywhere. And, so, the appeal to an authority like the Oxford English Dictionary can only be an appeal to ONE definition (or, more appropriately in the case of the OED, an appeal to the history leading to the current definition). We need MORE than that kind of an approach in this fractious time. The conversation between Tippett, Patel and Tretheway, it should be noted, did not trend towards a "single definition" -- exactly the opposite in fact. They all pushed for MORE dialog, greater understanding of the diverse opinions.

Later in the same day that I heard that conversation, I led a workshop at DU on Appreciative Inquiry. As I went over the "Eight Assumptions of Appreciative Inquiry", I could not help but recognize the overlap. Assumption #3 is "Reality is created in the moment, and there are multiple realities"; assumption #7 is "It is important to value differences."

"Multiple."

"Differences."

Appreciative Inquiry is a system, or methodology, for managing change. We know change is difficult (we're certainly experiencing both the change, and the difficulty!). Change, however, is inevitable. And we need to muster all of our resources to negotiate. To move to something new requires all of our voices. But it also requires all of our ears; we need to listen to other experiences, other beliefs, other hopes. We can't afford to let ONE definition blow another one out of the water. We must be better, we must be wiser than that.

Blessings,

Gary

Friday, October 21, 2016

Well, what do we expect?

In a wonderful interview* with Krista Tippett of "OnBeing", New York Times columnist and NPR commentator David Brooks tells of an encounter with a group of corporate Chief Financial Officers. His address to them followed his work on (if not publication of) his last book, The Road to Character (Random House, 2015). One of the chapters focuses on Dorothy Day, the social activist and Catholic convert. That chapter was apparently on his mind as he stepped in front of the gathering of (as he describes them) grey-haired white men who had just been discussing all things financial. He reflected (in the interview) that he wondered WHAT IN THE WORLD he would have to say to this group of hard-cored businessmen. Much to his surprise, as he began talking, the room grew profoundly quiet. He discerned that these people were hungry for something that went much deeper than dollar signs, debits and credits. Despite their "success", there seemed to be something missing in their lives that a "holy woman" (in many people's minds) possessed, something that couldn't be bought.

Brooks' expectations were blown.

As I listened, my mind was drawn back to several churches I attended when I used to live in California (although I KNOW the situation is not unique to that part of the country). All of these churches were attended, primarily, by very well-to-do people. Indeed, the parking lot of one of them was crowded on Sunday mornings with Rolls-Royces, Jaguars, Mercedes-Benz's, and perhaps a Bentley or two. CEO's and CFO's, engineers and bankers, filled the pews (much like Brooks' audience). I initially had the sense that this congregation was a place "to see and be seen". And it might have been that.

It might have been that. And, perhaps, for some it was. But this congregation had chosen, in the mid-1980's, to continue using a particular worship style that employed traditional language -- when most of the rest of the (national) church had gone to a more contemporary style. Certainly one could argue that these were "conservative" people, equating their politics with their liturgical preferences. And, again, for some that may have been the case. But the traditional language that they preferred also characterized the congregation as quite needy and sinful.** That is, as the congregation prayed, they "acknowledged and bewailed" their "manifold sins and wickedness" that they had "grievously committed by thought, word and deed" (The Book of Common Prayer (1979), 331). I would have thought that such a congregation would want to run and hide from such admissions.

My' expectations were blown.

Brooks' experience, as well as my own, called to mind that not everything we see (or assume) about people is ALL that there is. Indeed, there is often a public persona that obscures (whether intentionally or not) a private set of desires, needs or fears. In the case of these folks, there seemed to a yearning for something that might provide interior meaning in an externally-focussed, and driven, world. Many of these folks were asking, "How do we deal with success, especially as we're not sure we 'earned' it?" Or, "We've succeeded! But why do we feel so empty?" Or, "We've been given such a responsibility to steward these resources! What if we blow it?" Hard questions, and even raising them may make the individual questioner seem "weak", not knowing "all". At their best, our religious traditions help answer those questions, and, certainly, earlier generations seemed to understand that. The same understanding, research data seems to suggest, isn't shared by many folks today. But, Brooks, early in the interview, comments that, in his experience, a certain level of dissatisfaction with religion among younger people is countered by an interest in things interior. Affirmation, or building up, too, is sought, in a world that seems to devalue folks. "Affirmation" in connection with an admission of "sinfulness" might be seen as strange bed-fellows. But I think not. We are neither wholly wonderful nor wholly awful. But we do want to be accepted as whole. My suspicion is that the businessmen that Brooks encountered, as well as the church-goers with whom I shared a pew, were looking for a place to find that inner wholeness. And, apparently, it wasn't in a ledger, but a different Book.

Blessings,

Gary

* The section in which Brooks relates this encounter is in the "unedited interview" found at the OnBeing website. By the way, the interview is both with him and fellow NPR commentator E.J. Dionne.

** "Sin", while not a particularly popular word these days, figures pretty prominently in the Brooks/Dionne interview!

Friday, October 7, 2016

Those who make them . . .

The idols of the nations are silver and gold,

the work of human hands.

They have mouths, but they do not speak;

they have eyes, but they do not see;

they have ears, but they do not hear,

and there is no breath in their mouths.

Those who make them

and all who trust them

shall become like them.

These phrases, from Psalm 135 (vs. 15-18), always seem to strike a chord. The critique in the psalm, of course, is directed at Israel's/Judah's neighbors, but also to those within their own communities who might be tempted to follow the lead of those "nations". That temptation stemmed from uncertainty or uneasiness with the way things were going, and no visible, competent, leadership to provide direction or hope. As the saying goes, "Nature abhors a vacuum", and so the tendency was to fill that empty space with something.

It is easy, in our "advanced" twenty-first century, to look back on ancient peoples with a "pat-on-the-head" semi-condescension. Indeed, for several decades in the mid-to-late twentieth century, there was a belief among many sociologists (in the west) that modernism/secularism would supplant religion entirely. Many of those same scholars are now beating a retreat from that position, perhaps recognizing that the modern/secular positions don't address all of the significant questions people pose about the world and their place in it. On the other hand, we certainly have seen an exodus from organized religion over the last few years.

That exodus has been analyzed and explained in many different ways -- dissatisfaction with a linkage between some religious groups and conservative politics; horror at a seeming focus on retrenchment in the face of justified criticism (e.g., the sex abuse scandal in the Roman Catholic church); disgust in seeing a passion, on the part of some, for raising obscene amounts of money that do little to alleviate significant social problems; and, yes, an acceptance of "scientific" answers to the questions of human origins that come into conflict with scriptural answers. Yet many of those who depart "organized religion" still claim to "believe"; the common phrase "spiritual but not religious" does define many. And we see them searching for some kind of answers to their longings.

Many, of course, DO find answers in a secular/humanist world-view, and it is not my intent to criticize them. But I do think that the verses above apply to them as much as they do to people of faith. When we build answers to questions relying only on our own limited resources/knowledge, the answers rarely stretch us to the best of our capacities. The answers of our sacred texts often both inspire and confuse me. The inspiration isn't hard to explain. But WHY would people preserve texts that were critical of themselves . . . unless those texts supplied answers that weren't self-evident. And those answers rarely looked like the people as they were, but called them to be more.

Blessings,

Gary

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)